By John DeVoe with Tommy Hough

The Deschutes, Rogue, and Klamath rivers. The Willamette and the McKenzie. Much of WaterWatch’s work protects and restores cold water habitat on these iconic Oregon rivers. But that’s not all WaterWatch does.

WaterWatch has a 40-year tradition of protecting and restoring smaller, more intimate and remote streams no less critical for fish and wildlife, but often off the beaten path — tucked away in corners of Oregon that, for many of us, may take some effort to visit. Here are six examples of WaterWatch’s work to protect and restore lesser-known places that matter a great deal for fish and wildlife, biodiversity, and climate resilience in Oregon.

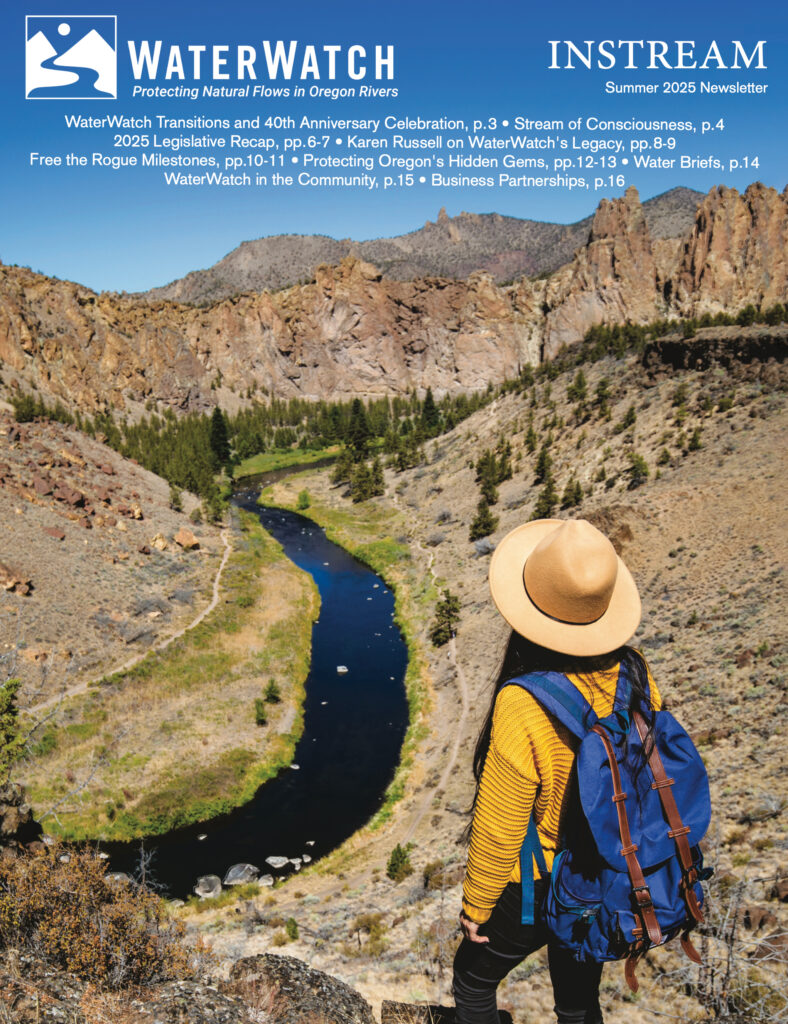

Author Ted Leeson called the Logan Valley a “stunningly beautiful mile-high meadow at the foot of the Strawberry Mountains,” and compared it to Yellowstone as “an open expanse of summer-green grasses and wildflowers, rimmed with lodgepole.” It was here WaterWatch protected streamflows in the headwater streams of the Middle Fork of the Malheur River, including Big Creek, McCoy Creek, and Lake Creek, all of which support abundant redband and bull trout.

Agriculture sought almost 19 cubic feet per second of surface water rights to flood irrigate these streams, mostly from Big Creek, despite the presence of three senior instream water rights downstream and no water available except in March, April, and May. At that elevation and given the snowmelt patterns in the area, there was no beneficial use of the water that could be made in those months. The ground was already wet. Fortunately, WaterWatch prevailed in an administrative trial before the Water Resources Commission, which protected streamflows in these three streams and the mainstem of the Middle Fork of the Malheur, one of Oregon’s original Wild and Scenic rivers.

Whitehorse Creek flows out of the Oregon Canyon Mountains near the border with Nevada southeast of Steens Mountain. An important sanctuary for imperiled Lahontan Cutthroat Trout, the Whitehorse was administratively closed to additional diversions of water, but apparently that institutional knowledge had been lost by the relevant agency in Salem.

Oregon was prepared to issue new water rights to divert water out of Whitehorse Creek until WaterWatch challenged the proposed approval, in part, by noting the existence of the administrative closure order. After WaterWatch filed its challenge, our office received a sheepish phone call from the state. Could WaterWatch, possibly, provide a copy of the closure order, since that order seemed to be unknown to the relevant agency personnel? Why yes, as a matter of fact, we do have a copy of the closure order and will be happy to forward it to the state. Case closed.

The Little Applegate River is a nursery for Rogue Basin salmon and steelhead. Yet in times of drought, agricultural water use could disconnect the Little Applegate from the Applegate River. WaterWatch completed several water transactions on the Little Applegate that transferred the most senior agricultural water rights to instream use and allowed the agricultural users to switch their water source to a reservoir in the area. As a result of these transactions, the most senior water rights on the Little Applegate now support instream use and the Little Applegate and the Applegate remain connected, even in years of drought and with a changing climate.

Author Maddy Sheehan describes Mill Creek, a tributary to the Walla Walla River, as “a beautiful, pristine trout stream . . . that abounds with rainbow and bull trout.” Mill Creek also serves as a source of municipal water for the City of Walla Walla, Washington. WaterWatch challenged efforts by Walla Walla to develop more water from diversions near the top of the Mill Creek watershed. A settlement moved the City’s diversions far downstream, and set aside specific amounts of streamflow by month in over 17 miles of Mill Creek to protect cold water habitat for these vital fish.

Flowing from Tenmile Lake to the Pacific Ocean, Tenmile Creek connects imperiled coastal coho salmon and other species from the open waters of the Pacific Ocean to Tenmile Lake’s fresh water spawning and rearing habitat. A permit application filed by the Coos Bay-North Bend Water Board to divert water from Tenmile Creek was challenged by WaterWatch for its potential impacts on fish and wildlife, and because the water board couldn’t show a near-term need for the water.

Like many municipal water providers, the water board didn’t plan to comply with development deadlines for new water rights, and instead sought multiple extensions of time to use the water by relying on an outdated public interest analysis done when the water right was issued. At the time, Oregon wasn’t enforcing development deadlines in water rights and routinely granted extensions of time to develop water rights long after certain deadlines had expired. Extensions of time to develop water were approved even though there was little or no evidence the water right holder had taken any steps to develop and put the water to beneficial use, as required by law.

Our case went to the appellate courts where WaterWatch won. This prompted legislation that extended certain development deadlines but required Oregon to condition this type of municipal water development to “maintain the persistence” of fish listed under either the federal or state Endangered Species Act. Eventually, the case was settled. WaterWatch secured additional protections for Tenmile Creek in the settlement with a 75 cubic foot per second bypass flow requirement so fish could pass the diversion, and a requirement that the mouth of Tenmile Creek be open to fish passage before any water use could take place.

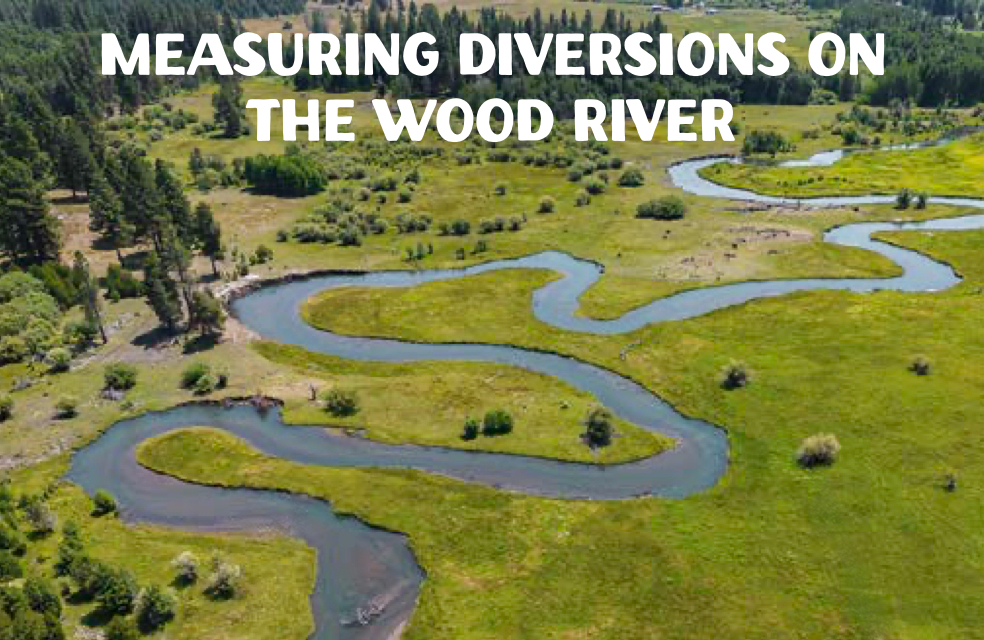

The Wood River near Fort Klamath is a gem of a river. Intimate in scale, trout fishing can be, shall we say — interesting. When streamflows appeared to be suffering on the Wood, WaterWatch launched a project to measure every out-of-stream diversion on the river. And what did we find? A report that documented this work demonstrated that, on average, measured diversions were exceeding permitted water rights by about 30 percent.

The report — and our advocacy — convinced Oregon to issue headgate notices to water users on the Wood, which required the installation of measurement devices at each diversion. Follow-up work documented that streamflows had increased the following year by 30 percent. The state asserted this increase was purely coincidental. Perhaps. But we all know better.

While you may or may not visit these places, they are important for fish and wildlife, and for biodiversity and climate resilience here in Oregon. These are just some of the examples of WaterWatch’s work on some of Oregon’s lesser-known treasures. There are many, many more. We are proud of our 40-year tradition of protecting and restoring such places.

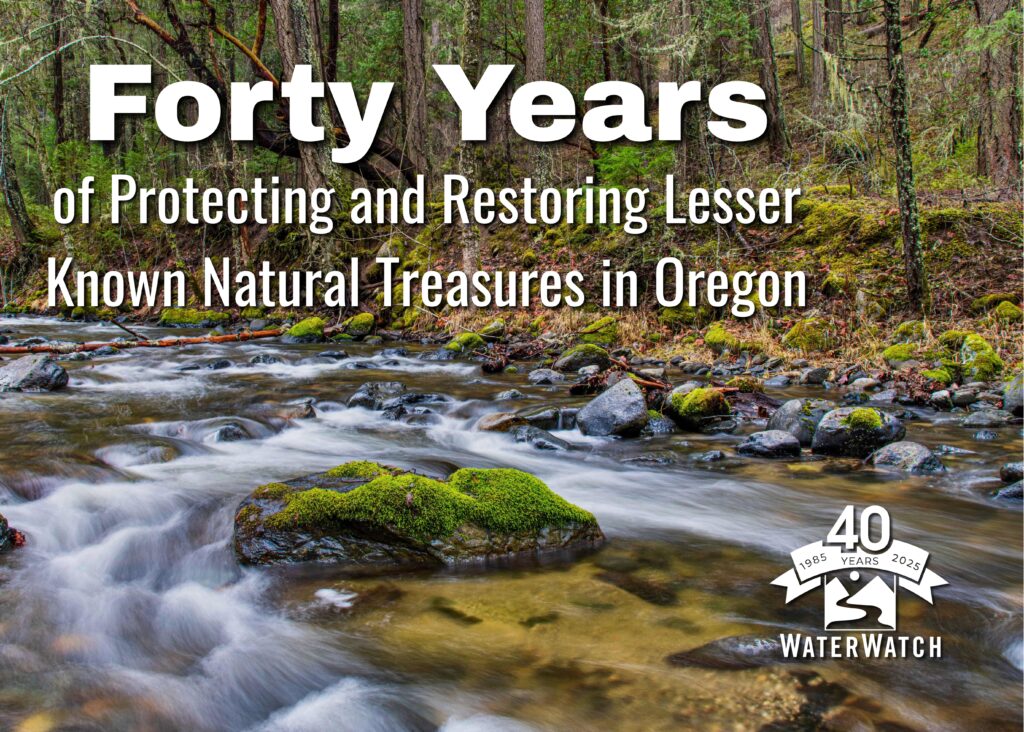

This article originally appeared in the summer 2025 issue of WaterWatch of Oregon’s Instream newsletter.

Individual “chapter” headings and Instream cover design by Monet Hampson. Banner photo of the Little Applegate River courtesy of Kyle Sullivan / U.S. Bureau of Land Management.