By Mateusz Perkowski | Dec. 12, 2025 | Capital Press

Critics of the state’s adopted plan say it doesn’t protect the region’s ag-based economy.

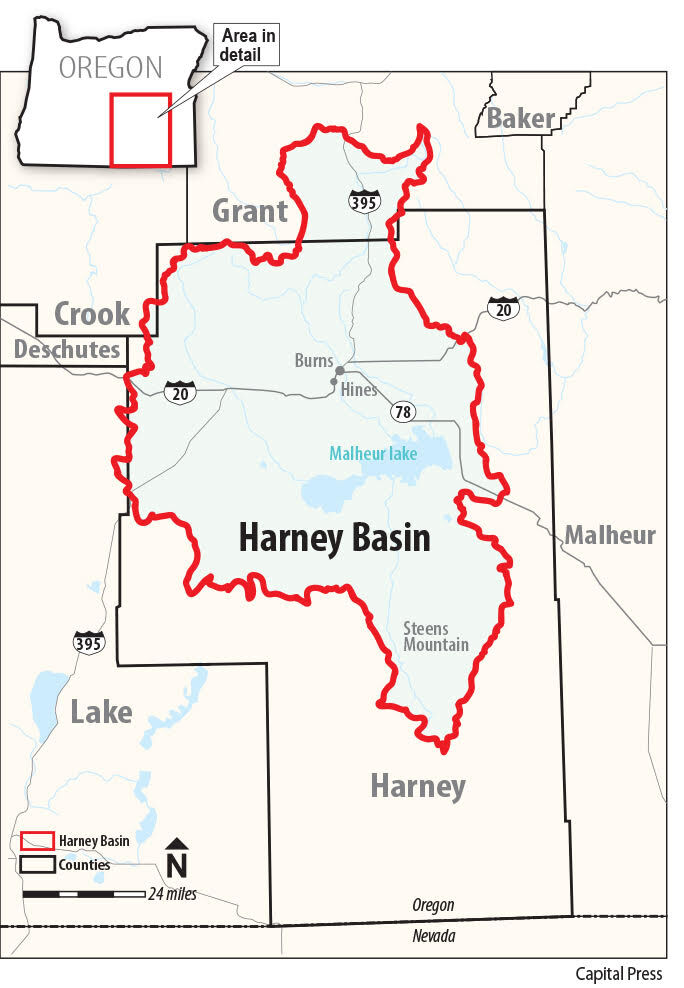

A petition seeking alternative rules to stabilize groundwater levels in Oregon’s Harney basin has failed to persuade regulators, who instead adopted the strategy preferred by a state agency.

Though the Oregon Water Resources Commission incorporated elements of the petition into their plan, critics say those changes don’t go far enough to protect the region’s economy.

Supporters of the petition, who include irrigators, cities and others in the area, also complained their alternative was given short shrift compared to the state government’s plan.

“Unfortunately, this process kind of devolved into a pissing match between the people of Harney County and state bureaucracy, with the Water Resources Commission caught in the middle,” said Robert Frank, a Harney County commissioner.

The petition for alternative rules wasn’t given equal footing with the plan put forth by the Oregon Water Resources Department, which is overseen by the commission, according to critics.

For example, the commission voted on the petition only after the OWRD’s regulations had already been approved on Dec. 11, and public comments on the competing proposals were not heard until after both decisions were made at the meeting.

“The petition amendment that the people of Harney County brought forward with a real strong unified voice to say, ‘This would better serve the people of Harney County,’ was given literally no thought today,” Frank said. For about a decade, the OWRD has been studying and considering regulations for the Harney basin after determining that groundwater was being pumped out at a higher rate than it was being naturally recharged in much of the area.

That process culminated in the agency proposing “critical groundwater area” regulations for the region — allowing irrigation other forms of water consumption to be curtailed — which critics argued would devastate the agriculture-dependent economy.

Under the OWRD’s regulations, the “permissible total withdrawal” of groundwater in the basin would be decreased by as much as 75 percent across seven sub-basins, with an overall reduction of 35 percent for the entire area over 30 years.

The plan includes “adaptive management” components under which planned reductions can be revised if groundwater levels recover more quickly or slowly than anticipated.

Stakeholder Petition

Irrigators and others submitted a petition to the commission earlier this year calling for an alternative strategy, in which the area would be divide into five sub-areas — only two of which would require mandatory reductions of 30 to 54 percent. The other three sub-areas would initially rely on voluntary cutbacks intended to reduce consumption by 10 percent over 15 years.

Since the petition was submitted in September, the OWRD altered its own plan to include some elements from the alternative strategy, such as exempting cities and the Burns-Paiute Tribe from the curtailments and removing the cap on consumption from one of the seven sub-basins.

Despite these changes, critics said the petition was not given sufficient consideration in how it was presented to the commission over the past three months.

“Our communication has been pretty limited throughout this whole process,” said Frank, the county commissioner. “It’s been the commission talking to the staff and the staff talking to the commission, and never having a chance to question.”

Regarding the substance of the rules, critics argue the OWRD’s plan has swept areas with less severe aquifer declines into a strict regulatory regime meant to halt the steepest levels of depletion, unnecessarily harming farmers and others for relatively minimal gains.

“The question we have is, why? What were you thinking?” asked Mario Patrelle, a Harney County resident. “Everyone must participate in the solution, but to correct the problem someone else has created.”

Members of the commission defended their unanimous vote for the OWRD’s preferred plan, saying it was responsive to the petition’s recommendations and other public comments collected during extensive outreach efforts.

Businesses at Risk

Farmers have repeatedly testified that they want to preserve their business and way of life for their children, which the OWRD’s plan is also trying to achieve, said Janet Neuman, a commission member and retired water law attorney.

“If the water is gone in 30 years or 50 years, it’s not going to happen,” Neuman said. “Not taking fairly aggressive or assertive action, at this point, will also hurt.”

The strategy proposed by the petition was overly reliant on such measures as buying water rights from irrigators, for which the OWRD cannot guarantee funding will be available, she said.

“I don’t think these rules are the right place for that,” she said.

Joe Moll, a commission member and executive director of a conservation nonprofit, said it’s “admirable” that OWRD included an “adaptive management” strategy that will allow the agency to respond to the success of voluntary cutbacks.

“We should be jumping up and down for that,” he said.

When asked what the OWRD and commission should do now that the agency’s preferred plan has been adopted, Rep. Mark Owens, R-Crane, said that regulators can still avoid the harshest economic impacts by delaying enforcement in areas with less drastic aquifer declines, to give voluntary measures time to work.

“We can figure out how we can limit arguments and litigation, or we don’t,” he said.

This article originally appeared in the Dec. 12, 2025, issue of Capital Press.