By Alec del Pino Gil-Casares | Dec. 26, 2025 | Harvard Political Review

While prompting your AI chatbot does not directly use water, many data centers rely on evaporative cooling to keep their computing chips, in charge of processing, manipulating, and transforming data, at a functioning temperature, consuming millions of gallons of potable water every day. Indeed, the chips require almost as much power for cooling as they do to run: 40 to 45 percent of the data center’s energy goes to cooling, says Toni Atti, CEO of Phononic.

Importantly, the water data centers consume does not return to its system to be reused; instead, it is evaporated, so data centers constantly need more. According to Shaolei Ren, an associate professor of electrical and computer engineering at UC Riverside investigating the health toll of AI, data centers consume “the same water people drink, cook, and wash with.” Google, for example, acknowledges that out of the 8.1 billion gallons of water its data centers consumed in 2024, 7.2 billion were potable. That same year, 87 percent of water Apple withdrew was potable. When this water is evaporated, populations are deprived of the potable water they require to thrive.

Moreover, a UC Riverside report on AI’s water usage shows Big Tech’s water consumption continues to rise; from 2022 to 2023, Google’s data center water consumption grew by 17 percent and Microsoft’s by 22 percent. The researchers estimate that Microsoft’s U.S. data centers may have directly evaporated 700,000 liters of clean freshwater while training OpenAI’s GPT-3 language model in addition to increasing water demand at power plants which support AI data centers, further pressuring the resource.

Often, states with the most concerns regarding water, such as Texas, California, Nevada, Arizona, and Georgia, also attract a high density of data centers. As water is cheaper than electricity, companies elect to build their data centers in areas with lower power costs, completely disregarding their water shortages. The regions most in need of water end up shouldering the worst of Big Tech’s worrying water-hunger.

In Reno, Nevada, where ten major AI companies are already operating or constructing data centers, NV Energy’s report outlines 12 new data center projects between now and 2033 that will necessitate nearly six gigawatts. They could consume between 860 million and 5.7 billion gallons of water annually in the nation’s driest state and, given the extra electricity that will need to be generated to run the data centers which consumes even more water, that number could rise to 21.2 billion gallons total per year — almost twice as much as San Francisco’s yearly consumption.

The rapid build-out of water-hungry data centers in a region already suffering from severe drought, overused groundwater, and rising temperatures is sparking concern among residents, environmental groups, and tribal communities. The Truckee River, the main water source for the region, ends at Pyramid Lake on the Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe’s reservation, placing their community directly in the path of these growing pressures.

“We have seen the devastating effects of what happens when you mess with Mother Nature,” said Chairman Wadsworth of the Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe. “Part of our spirit has left us. And that’s why we fight so hard to hold on to what’s left.” He worries the increased water draw could force the tribe into another chapter of what he calls “a century of water wars” to defend their lake and legal rights.

Kyle Roerink of the Great Basin Water Network echoes the alarm, warning that letting corporations “stick more straws in the ground” without oversight could drive water policy in the wrong direction. “If pumping [extracting water from the lake to a higher reservoir to store energy] does ultimately exceed the available supply, that means there will be conflict among users,” Roerink added. “Who could be suing whom? Who could be buying out whom? How will the tribe’s rights be defended?”

Moreover, there are statewide implications beyond tribal lands. At the same time as the Sierra Nevada snowpack — an indispensable source of water during warmer months — is shrinking due to climate change, water demand from data centers is spiking. Given that data centers and the public often draw from the same sources, this tension threatens to push the region toward deeper scarcity and conflict. Sierra Club Toiyabe chapter director Olivia Tanager argues that, “Nevadans, in particular, should be concerned … because of the impacts to … our shared climate and conservation goals.”

Yet AI companies like Microsoft, Google, Amazon, and Meta have promised to become water positive by 2030, meaning they will replenish more than the water they consume. While this is an encouraging goal, these big names cannot forget about the small neighbors they most impact. Replenishing water in Madrid, Spain or drilling a new well for clean water in Curacaví, Chile can change the lives of those populations, but it does nothing to improve the situation of those in Nevada, who are currently being left to fend for themselves.

In The Dalles, Oregon, a small city already grappling with a multiyear drought, Google’s data centers have become imposing giants in the local water system. Over the past five years, the company’s water use has nearly tripled, and its data centers now consume more than a quarter of all the city’s water. Just as in Nevada, as Google moves forward with plans to build two more data centers in The Dalles, alarm is growing among local tribes, environmental advocates, and residents who fear the strained water supply cannot sustain further industrial expansion.

John DeVoe, former executive director and senior advisor at WaterWatch of Oregon, warns that Google’s “demand comes on the heels of a fully allocated system,” adding that Google uses enough water annually in The Dalles to flood the entire city under three inches of water. Many worry about the potentially devastating consequences on local ecosystems, such as Elaine Harvey of Yakama Nation Fisheries who fears the “impact on the plant life, fish life, wildlife, and the community.”

Adding to public frustration is Google’s push for secrecy. When city attorneys sued The Oregonian to block the disclosure of Google’s water use in The Dalles, the company paid more than $100,000 to support the city’s legal efforts, arguing that the data constituted a confidential “trade secret.” It was only after The Dalles settled with The Oregonian that the tech giant disclosed its water use in data centers for the first time.

The Oregonian case is not alone in demanding transparency from AI companies. Scientists, research facilities, activists, non-profit organizations and software companies believe that Big Tech should disclose more detailed information about their activities. The current lack of knowledge on how data centers’ water consumption affects local communities and ecosystems enables tech giants to hide from the consequences of their own actions. Indeed, better public understanding is essential to allow organizations and lawmakers to effectively protect their people.

Ultimately, the gallons lost to cooling the servers that answer our prompts are drawn from someone’s tap, someone’s river, someone’s right to clean water. Like The Oregonian, we ought to demand transparency from Big Tech about their water consumption and, like the Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe, we must urge AI companies to prioritize regional responsibility to both the people who are suffering because of them, and the environment they are abusing for their artificial ambitions.

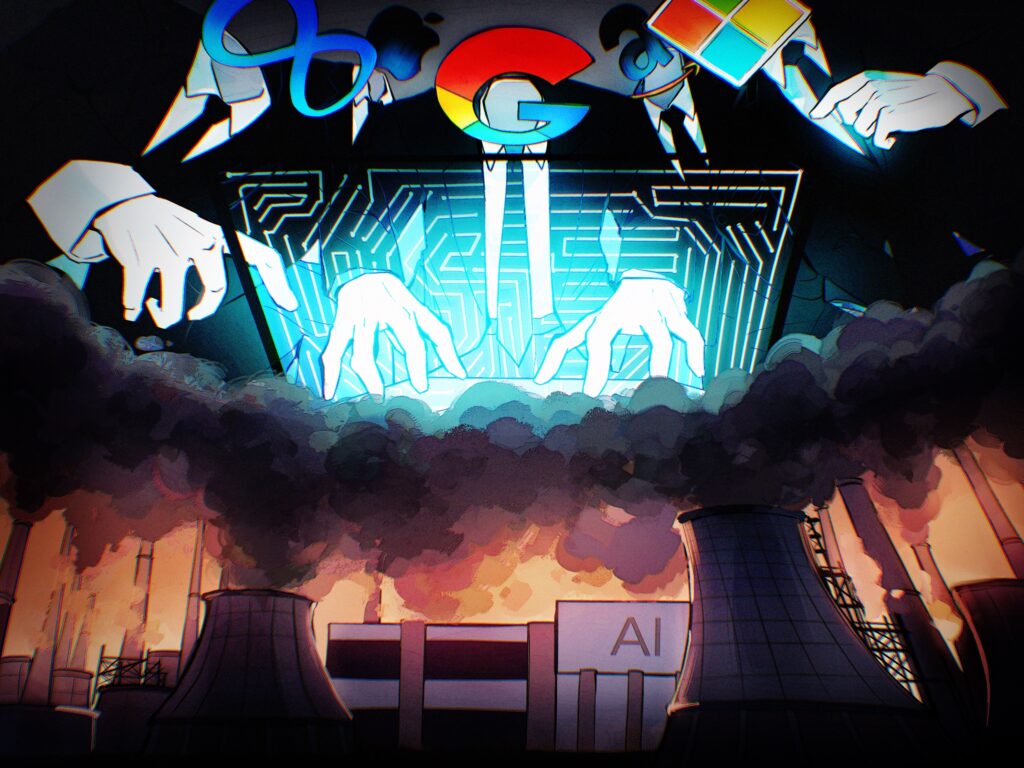

This article originally appeared in the Harvard Political Review on Dec. 26, 2025. Illustration by Felicity Wong licensed for the exclusive use of the Harvard Political Review.