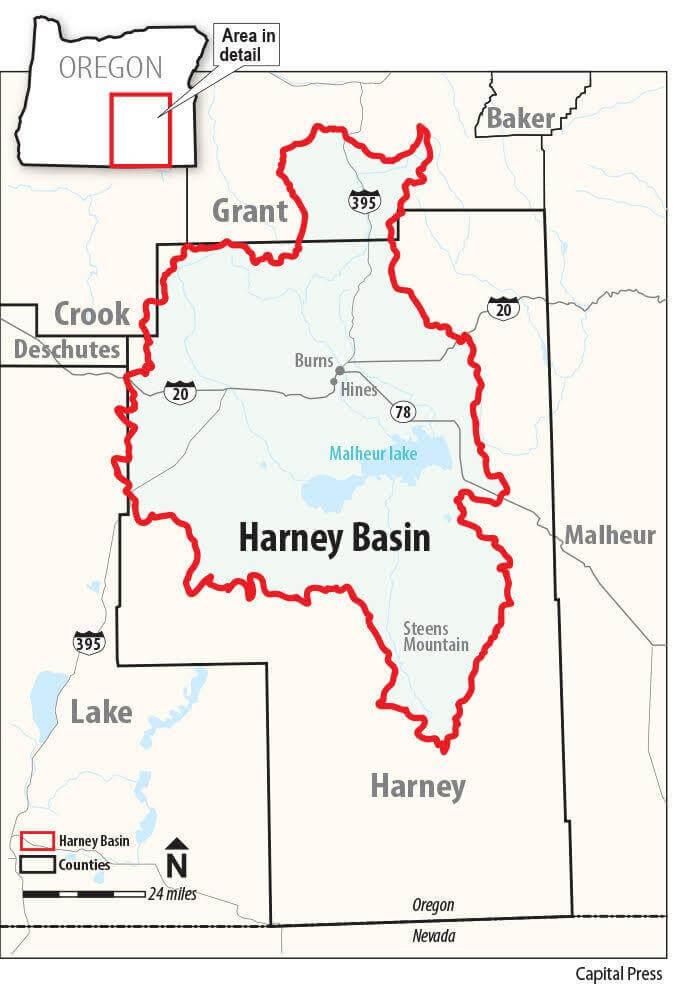

By Matuesz Perkowski | Dec. 24, 2020 | The Other Oregon

Agriculture in Oregon’s Harney Basin faces a situation akin to being chased by an aggressive dog, according to farmer Mark Owens.

Irrigators realize it’s going to hurt, he says, but they won’t know how much until it actually “bites them in the ass.”

“Change is on the way and they know it,” said Owens, who also represents the region in the Oregon House.

In reality, even an entire pack of ferocious canines would probably be preferable to the problem Harney Basin farmers have actually encountered: Groundwater declines are steep enough to potentially require severe pumping curtailments — a threat to their individual livelihoods as well as the region’s broader economy.

Now, the question is how Oregon’s water regulators will deal with excessive groundwater withdrawals in the long term.

Will the Oregon Water Resources Department begin shutting down irrigation wells? Or will the agency agree to a plan aimed at slowing the aquifer’s decline developed by a collaborative group of farmers, conservationists and others?

For farmers like Owens, who grows about 3,000 acres of alfalfa around Crane, the state government’s approach will determine whether they’ll continue to produce crops profitably in the remote high desert basin.

“Harney County has allowed me to live the American Dream, and I’ve done it through groundwater extraction,” he said.

Water regulators have already stopped issuing new well-drilling permits, causing consternation among farmers, but actually reducing groundwater declines is expected to require more drastic measures.

In Oregon, the ability to irrigate depends on the “priority” of a farmer’s water rights, commonly referred to as “first in time, first in right.” Those “senior” irrigators who established their rights the earliest can request that OWRD shut off “junior” water users to conserve the resource.

“Regulating folks off based on priority date lays waste to the community,” said Brenda Smith, executive director of the High Desert Partnership, a nonprofit involved in the collaborative.

Owens and other growers involved in the collaborative process hope to avoid such regulation, which would cost some irrigators their livelihoods.

“What we need to figure out is how to get there through management, not regulation,” he said. “When the state shuts you off, you can’t use a third less, you can’t use half — you’re gone.”

While it will also be tough, the preferred path forward may require farmers to voluntarily agree to decrease their water usage.

Such a reduction could be made possible with investments in more efficient irrigation equipment that uses less water because the nozzles hang below the crop canopy, reducing evaporation.

Another option may involve the adoption of alternative crops, such as grass seed, small grains, hemp and carrot seed, which have a shorter irrigation season than the basin’s ubiquitous alfalfa.

Native seeds are an attractive possibility because they’re in demand among federal agencies to restore rangeland and are often ready to harvest before irrigation is necessary, said Smith of the High Desert Partnership.

“They go dormant when rainfall naturally stops in summer,” she said.

While the collaborative’s eventual plan would be better for farmers than state water regulation, the concept of managing water in this way is unprecedented in Oregon, Smith said.

For the idea to work, it will likely require more time, money and research than regulators had intended when initiating the collaborative process, she said.

“We’ve definitely opened a can of worms,” Smith said. “It’s a lot bigger than anyone realized.”

Another question is whether the disparate interests of people involved in the collaborative will prevent them from reaching a consensus, and whether other irrigators will accept an eventual plan.

Without incentives to pay for irrigation investments, for example, some irrigators who don’t face immediate regulation may resist voluntary agreements, Owens said. “A lot of farmers and ranchers with the oldest water rights will wonder why they need to reduce.”

There’s also been backlash to a potential collaborative plan among other growers, who see the process as aiming to protect senior water users, said Shane Otley, a rancher and farmer near Burns who’s involved in the process.

But the reality is they’ll either have to enter into voluntary agreements or face OWRD regulation, Otley said.

“We’ve made it black and white for people,” he said. “We’ve got two options. Which option do you want?”

Nonetheless, Otley said, the collaborative process can be frustrating for irrigators, who are eager to arrive at a plan after roughly five years of negotiations.

Despite sitting in a six-hour meeting, it sometimes feels like only about five minutes of work have been accomplished, he said. Meanwhile, farmers aren’t paid to attend such meetings, unlike representatives of the government or nonprofits.

“They don’t care how long this process drags out,” Otley said.

Irrigators have little choice but to remain invested in the process, as shutting farmers down based on water rights priority would devastate the community, he said.

“Water is their lifeblood,” Otley said.

As environmental advocates point out, though, allowing the status quo to persist in the Harney basin isn’t an option.

Healthy water levels in aquifers feed wetlands and springs while lowering the temperature of streams, all of which is important for fish, wildlife and plant species, said Lisa Brown, an attorney with the WaterWatch of Oregon environmental nonprofit, which is involved in the collaborative.

“Groundwater provides important ecological benefits,” Brown said. “There is an ecological cost to declining groundwaters.”

In the end, water regulators will likely need to establish a “critical groundwater area” — which allows restrictions on authorized use to mitigate over-appropriation — while working with the collaborative on strategies to achieve a sustainable level of withdrawals, she said.

It’s probable that the basin is facing “severe decreases” in groundwater pumping, though agreeing on the exact level of reduction is difficult, Brown said. “Those are hard conversations. We’ve talked around it but haven’t addressed it head-on yet.”

The Oregon Water Resources Department will begin asserting a more hands-on role in the ultimate decision next year, when the agency plans to convene a “rules advisory committee” to start devising new regulations for the basin.

The process will be guided by a groundwater study by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), which is expected to provide a detailed “budget” of water discharges and recharges in the basin by the end of 2020.

Preliminary results of this “hydrogeological framework” indicate the basin as a whole is losing about 80,000 to 90,000 acre-feet a year, said Stephen Gingerich, a research hydrologist with the USGS. An acre foot represents the amount of water needed to cover an acre at the depth of one foot.

Though roughly 150,000 acre-feet are pumped out of the system a year, mostly for irrigation, the net loss is reduced by natural groundwater recharge, he said.

“The bottom line is there seems to be a lot more pumping than recharge coming in,” Gingerich said.

The situation is uneven across the Harney Basin, since some areas are more out of balance than others due to variations in pumping levels and geological formations, he said.

A significant consideration is that much of the aquifer’s water infiltrated the ground thousands of years ago, possibly because the region was once home to a large lake during the Pleistocene Epoch, he said.

“Most places across the basin, we saw very old water. There’s very little young water in the lowlands,” Gingerich said. “A lot of the recharge getting into the system isn’t getting to the lowlands where everyone is pumping.”

As a result, the Weaver Springs area of the basin is now seeing groundwater levels decline by up to 10 feet per year, he said. Though the aquifer may be 3,000 to 5,000 feet deep, wells wouldn’t be practical to dig to that depth, particularly since the bottom may consist of compacted sediment from which water is tough to extract.

An increased demand for alfalfa spurred more drilling for water in recent decades, though water regulators didn’t stop issuing new well permits until 2015, after receiving objections due to concerns about groundwater declines in Harney Basin.

“The speed of development outpaced the data that we were getting back,” said Justin Iverson, OWRD’s groundwater section manager.

Declaring the basin a critical groundwater area would allow the agency to curtail existing uses, but the agency wants to explore other strategies to decrease groundwater use, said Racquel Rancier, OWRD’s senior policy coordinator.

“We’re looking for opportunities for voluntary reductions,” she said.

Despite the challenges involved in creating a voluntary plan to stabilize groundwater declines, it’s better than the alternative, said farmer Mark Owens.

“Are we going to get to a consensus in the end?” he said. “I don’t know, but we’re trying.”

This article originally appeared in The Other Oregon on Dec. 24, 2020.