April 4, 2023

By Jim McCarthy

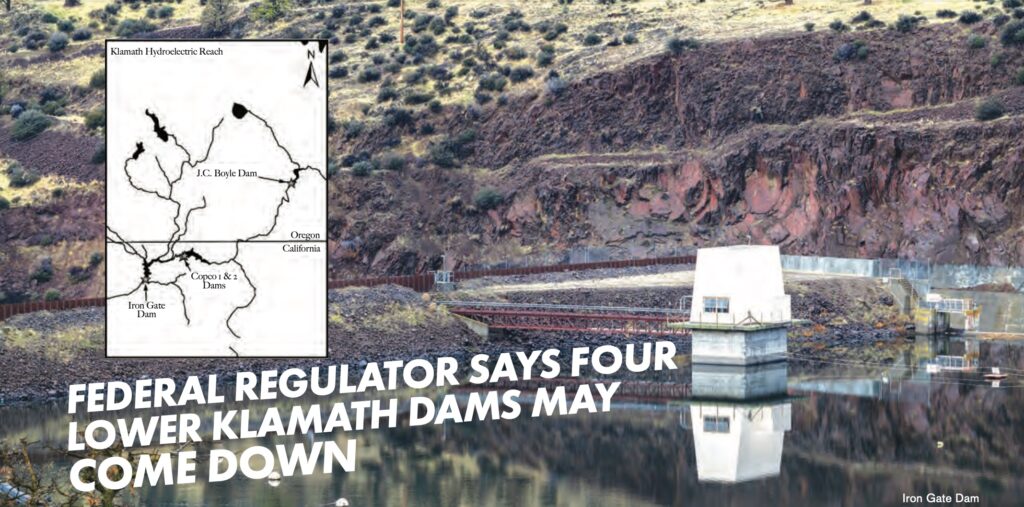

In Nov. 2022, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission granted final approval for the decommissioning of the lower four hydroelectric dams on the Klamath River near the Oregon-California state line. The decision marked the end of two decades of advocacy, politics, and bureaucratic processes surrounding this hydro complex. It is hoped that the smallest of the four dams, Copco 2, will come down this summer, and that the other three dams will follow soon after to open over 350 miles of habitat closed to native salmon and steelhead since 1918 in violation of tribal treaty rights — and common sense.

Klamath dam removal presents a major opportunity to restore important but dwindling fish runs vital to the region, Native American tribes, and coastal communities. This year, as in past years, a Klamath salmon collapse has sparked a salmon fishing disaster across the coast, resulting in tens of millions of dollars in lost economic activity, millions of pounds of lost seafood production, thousands of lost jobs, and the loss of world-class recreational opportunities. But dam removal alone cannot restore the Klamath and end the region’s woes. Restoration will require additional, essential steps.

These steps include providing adequate streamflows and lake levels to support abundant salmon and other native fish, improving fish passage at Keno Dam and other dams upstream of the soon-to-be former hydro complex or removing these structures altogether, protecting and restoring depleted groundwater reserves, and reclaiming converted wetlands to recover aquatic habitat and natural water storage while improving water quality. WaterWatch continues to advocate in public spaces, in the legislature, and in the courts for these essential steps towards the Klamath’s sustainable future.

WaterWatch began working towards Klamath dam removal well before PacifiCorp’s hydropower license expired in March 2006. Years before, WaterWatch had joined with Oregon Wild and other organizations to publicly expose and end an exclusive electric pumping subsidy funneling some $10 million per year to Klamath agribusiness at the expense of PacifiCorp’s other ratepayers. These powerful interests had succeeded in connecting this subsidy politically to PacifiCorp’s federal hydropower license when it was last renewed in 1956.

In 2006, Klamath agribusiness intended to quietly extend this lucrative and water-wasteful subsidy 30 to 50 years into the future alongside another federal license for the Klamath dams. In this situation, WaterWatch believed ending the pumping subsidy would not only improve water use efficiency in the Klamath, but would also remove a substantive reason for powerful agribusiness interests to support relicensing the Klamath dams.

By April 2006, WaterWatch and our allies had convinced the Oregon Public Utility Commission to rule against the subsidy after a months-long proceeding. The state legislature, over WaterWatch’s objections, then provided Klamath agribusiness a generous multi-year subsidy offramp period paid for by other Oregon utility ratepayers. With the subsidy question resolved in favor of river restoration, WaterWatch and Oregon Wild returned to the PacifiCorp dam relicensing negotiations advocating for our preferred alternative: a standalone deal to remove the four lower dams.

Unfortunately, over the following two years the George W. Bush administration took over as mediators in these talks. They excluded WaterWatch against our will due to our opposition to the Bush Administration’s Klamath Basin Restoration Agreement (KBRA), which required that dam removal wait until Congress passed the bloated and unworkable $1 billion KBRA package favoring agribusiness at the expense of taxpayers, fish, and the basin’s National Wildlife Refuges. While WaterWatch had joined Hoopa Valley Tribe and others to defeat the KBRA by 2015, the KBRA had by then delayed dam removal longer than even PacifiCorp could have hoped.

Generally, utilities can expect to delay federal relicensing decisions for 12 years while using interim annual licenses. The Klamath was ultimately delayed 17 years, and by 2016 a standalone dam removal agreement moved forward. WaterWatch is gratified this long-sought goal for many in the Klamath is within sight.

This article originally appeared in the spring 2023 issue of WaterWatch of Oregon’s Instream newsletter.