By Kelly House and Mark Graves | July 26, 2016 | The Oregonian: Draining Oregon

Oregon is helping farmers drain the state’s underground reservoirs to grow cash crops in the desert, throwing sensitive ecosystems out of balance and fueling an agricultural boom that cannot be sustained, The Oregonian has found.

Managers with the Oregon Water Resources Department (OWRD) handed out rights to pump water while pleading ignorance about how much was actually available. They have approved new pumping for irrigation even as their own scientists warned it could hurt the water table, interviews and state records show.

The amount of water Oregon farmers can legally extract now totals nearly one trillion gallons a year – enough to fill 150 million tanker trucks.

More than 5,000 farms in Oregon’s $5.4 billion agricultural industry rely on well water to survive. Nearly a million Oregonians need wells for water they drink.

The unending churn of water comes with consequences.

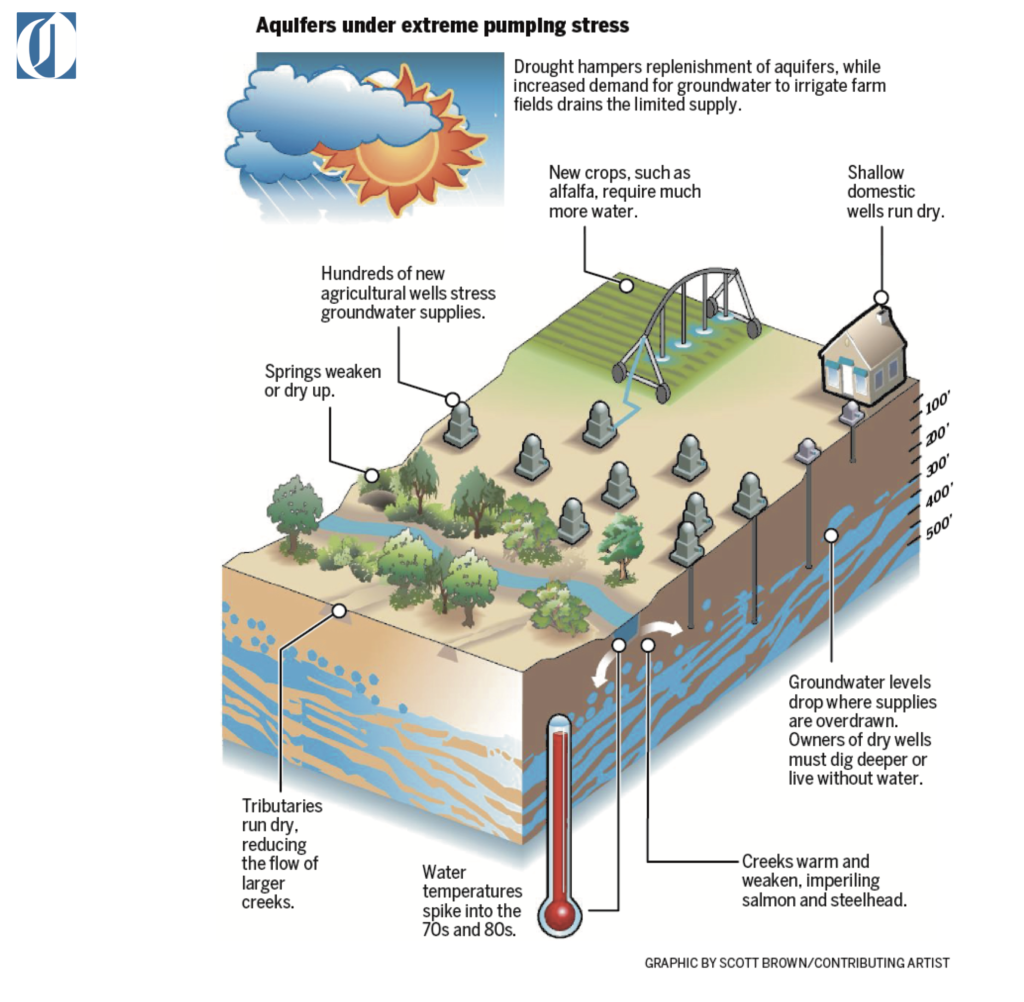

Overpumping Oregon’s underground reserves, known as aquifers, can dry up household wells and saddle farmers with huge costs to pump from ever-greater depths. It also jeopardizes 652 species of sensitive plants and animals. Victims include federally protected salmon and steelhead, whose recovery has failed to materialize despite a 25-year effort that’s cost taxpayers billions.

The Oregonian reviewed hundreds of documents, interviewed dozens of farmers, ranchers and water experts, and analyzed three databases covering thousands of water rights and wells.

Among the findings:

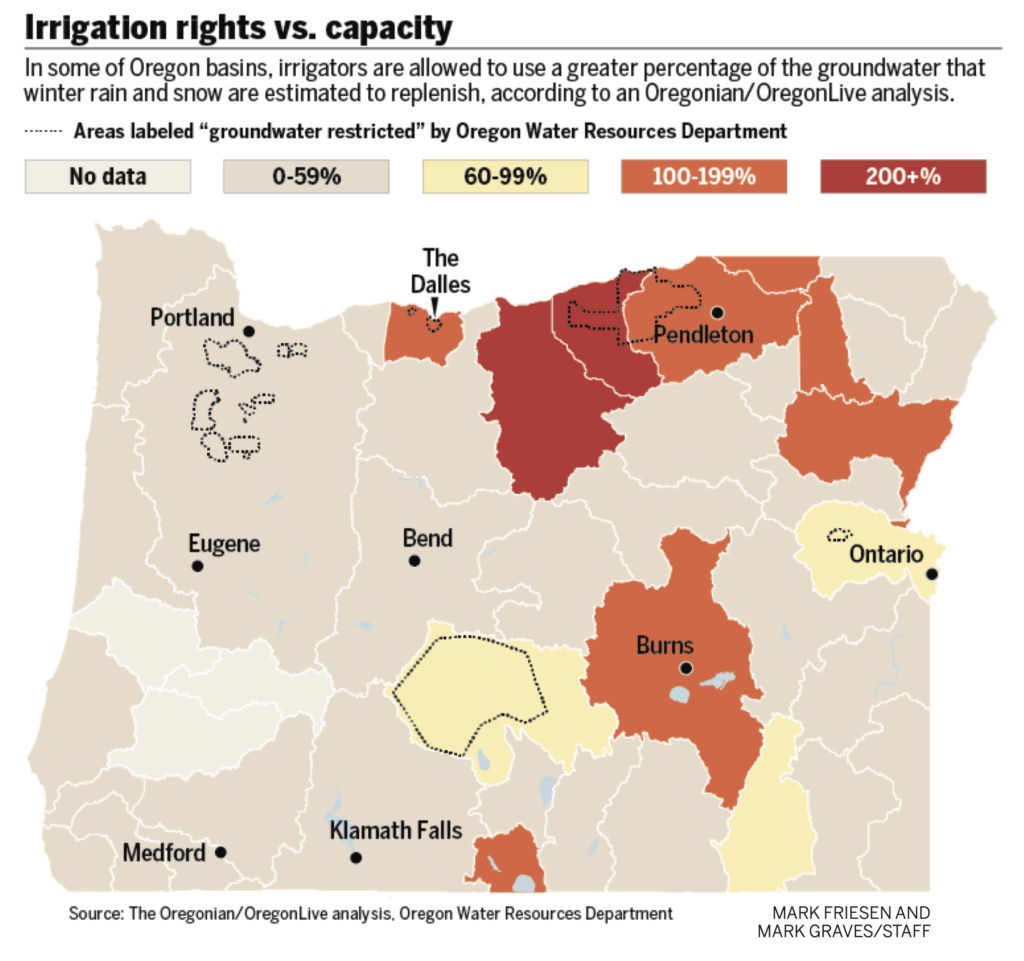

- Farmers in a quarter of eastern Oregon, the driest part of the state, are allowed to pump more underground water each year than rains and snows deposit. It’s one rough indicator of the mismatch between supply and demand. The shortfall was 49 billion gallons a year in the Willow Creek Basin of Morrow County. In southeastern Oregon’s Harney Valley, it was 11 billion gallons.

- It’s virtually impossible for the state to enforce its pumping limits. On all but a fraction of Oregon’s roughly 400,000 wells, owners have no obligation to disclose their actual water consumption. They are on an honor system not to exceed their allowance.

- Lawmakers routinely budget no money at all for studies to expand Oregon’s spotty knowledge of groundwater supplies. At current funding levels, the work won’t finish until 2096.

- Other parts of the country set a higher bar than Oregon for granting pumping rights. Washington state, for example, won’t allow a new well to be tapped if it could cause any harm to a stream that’s already hurting for water. Oregon, in contrast, will deny permits only in cases where the harm would be considered “substantial.”

Oregon water resources officials defend their decisions, saying all western states face challenges managing water. The regulators note that federal geologists completed the only statewide study of Oregon aquifers decades ago. They say it’s hard to accurately keep tabs on the underground supply without more money for staffing and research.

“We’re obligated to evaluate the applications, we’re obligated to make a decision timely, and then we have to defend that decision as well,” said Doug Woodcock, deputy director of the Oregon Water Resources Department. “And I think it would be difficult to close down all permit issuance in the state of Oregon until we had all of the information available for everywhere.”

Giving away water with abandon has failed Oregonians repeatedly. In river basin after river basin, officials over the decades took no action until aquifers had dwindled measurably. Regulators put on the brakes, and farmers, many of whom had bet on water rights for their livelihoods, lost out.

In the Umatilla Basin during the last 1980s and early 1990s, dozens of farmers lost access to their promised water under state orders. Farm values tanked.

“With one signature, how would you like to have $400,000 wiped off your net worth?” said Bill Doherty, a Morrow County farmer who sued the state over restrictions that took half his water supply and left him with $250,000 in debt on an unused well.

“Every time I get a wild idea, I just go out and look at that pump,” said Bill Doherty, a Morrow County farmer whose well had to be shut off. “But you can’t live with that bitterness. You just go on.” When the state moved in to shut off wells near Butter Creek to stem groundwater pumping that had lowered the groundwater table by dozens of feet, Doherty and his neighbors fought back. The farmers sued the state three times over its attempt to curb their use of groundwater to irrigate crops, and won twice.

Larry Campbell and his family could see the signs of overpumping years before the state stepped in.

Campbell’s father was a dryland wheat farmer in the Hermiston area all his life. But Campbell’s neighbors in the 1970s started turning to irrigated crops that can be several times more profitable, and he joined in. Two powerful new wells soaked 2,000 acres of beans, barley, alfalfa and safflower on the Campbell farm.

It wasn’t long before their wells lost steam. Rather than chasing the water deeper, Campbell, now 77, and his brothers chose to “get outta the fight.” They sold the farm.

The state’s pumping restrictions in the Umatilla Basin were supposed to be evaluated every five years. But regulators rarely have bothered. Oregon’s water agency can offer proof of doing such an evaluation only once in the past two decades. And the water table continues to fall, records show.

“Maybe at some point, all the wells will dry up, and everybody loses and goes back to dryland,” Campbell said. “It’s still good dirt.”

A Pro-Development Approach

The Oregonian analysis used a basic measure of the mismatch between supply and demand, comparing permitted use with annual replenishment.

The Oregon Water Resources Department labeled it “an overly simplistic and incomplete view.” Yet the same state agency, with some refinements, relied on similar calculations to justify halting new permits in the Harney Valley last year.

The new findings echo what environmentalists have long warned: that Oregon is giving away water at an unsustainable rate.

“We’re basically writing checks we know we don’t have money in our account to cover,” said Joe Whitworth, president of The Freshwater Trust, a Portland-based conservation group. “Eventually, they’re going to bounce.”

Consider how regulators evaluate applications to pump. A state reviewer fills out a form asking whether water is available to support a prospective well. Forms marked “cannot be determined” routinely get the go-ahead, a review of hundreds of permit applications shows.

“It’s certainly a pro-development approach,” said Ivan Gall, who oversaw the Oregon Water Resources Department’s groundwater program until moving to a different job in the agency this spring.

The water resources department has hesitated to say no to irrigators in the wake of threats from lawmakers and pressure from industry, according to agency critics and former employees. Conservationists say that rather than being a watchdog, the department is a revolving door with the water users it regulates.

Some irrigators are so confident their permits will be approved, they sink wells first and file the paperwork later. Andy Root, a Harney County rancher who began pumping without state approval, said it has long been common practice in the area. He’s since applied to obtain a water permit years after he began pumping.

Yet farmers and ranchers pay a price for the state’s failure to make hard choices. Oregon’s water agency has clamped down on groundwater use in seven basins since the 1950s, changing course after empowering well owners to begin draining down an aquifer.

The newest trouble spot is in Harney County, site of this year’s armed standoff at the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge. Records show state officials feared years ago that irrigation wells in the Harney Valley might be draining Malheur Lake, a vital stopover for threatened migratory birds. Yet the state kept issuing permits, more than 100 in the past seven years. Now, state officials believe they gave away too much. There’s talk of the state shutting down ranchers’ newly dug wells, a move that would have serious economic ramifications.

Oregon’s failures aren’t unique. Water tables are sinking across the West, from Washington to Arizona. A study last year found humans have overexploited many of the world’s largest aquifers.

Agriculture is the biggest water guzzler by far. In Oregon, it accounts for more than 80 percent of all use.

Our enormous demand will only grow. Global trade in Oregon beef, cherries, cheese and other goods is driving farm development across the high desert. At the same time, climate change is forecast to bring more and more droughts like the bone-dry summer of 2015, drawing streams down to a trickle and curtailing flows of rainwater to deep underground aquifers.

If Oregon is going to solve its problem with overpumping, time is running out.

Permanent Consequences

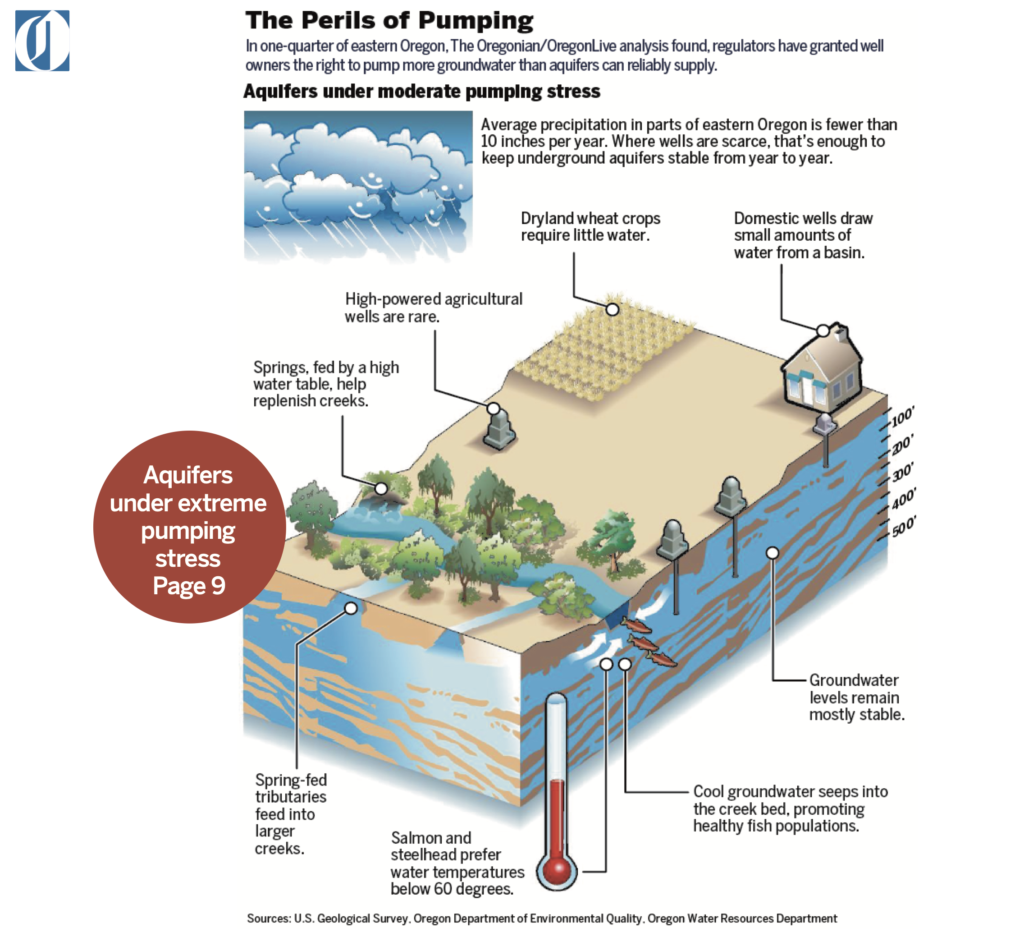

To grasp the damage that overpumping can do, it’s important to understand what makes the underground water supply essential.

Like subterranean sponges, aquifers are stores of water that percolate unseen beneath our feet, filling the spaces between sand, gravel and rocks. Rainfall that doesn’t drain into rivers, evaporate or enter plant roots ends up filtering into the soil, where it inches toward an eventual discharge point.

The water re-emerges as springs that sustain lush wetlands in the desert and keep rivers flowing after the summer snowmelt has tumbled out to sea. Fish, wildlife and plants thrive in the cool discharge. Taking water from the subsurface can rob these places and the animals that live there.

“There’s really no such thing as zero-impact groundwater pumping,” said Marshall Gannett, a groundwater scientist with the U.S. Geological Survey.

Because aquifers flow into streams, intensive well drilling can sap water from owners of existing wells while also depriving farmers who need surface water for irrigation.

A falling water table caused springs underneath the Lost River, in the town of Bonanza, to flow backward. The tiny city of Merrill was forced to truck in water when the aquifer dropped below municipal well pumps in 2010. Intensive groundwater irrigation was to blame in both cases.

In some Oregon streams, springs are such a vital component to surface water that nearly every riffle has its origins underground. Such is the case in the Metolius River, which surges out of the forest floor near the Central Oregon town of Sisters at a near-constant 50,000 gallons per minute.

Cool water seeping in from underground can be a lifesaver for salmon when summertime river temperatures climb to lethal levels. But overpumping across Oregon has worsened the odds for fish.

Allison Aldous, a scientist with The Nature Conservancy, measures the flow of a spring in the Ochoco Mountains. The area’s small, spring-fed wetlands sustain a diverse and lush micro-environment in an otherwise arid desert. Human-made diversions of the groundwater the feeds the springs have damaged or killed many such wetlands.

Thousands of spring-fed wetlands that dot the state are at risk, as well. These sensitive environments harbor rare plants and insects, including carnivorous cobra lilies and certain caddisflies found only in Oregon. Allison Aldous, a scientist with The Nature Conservancy, calls these wetlands “amazing warehouses of biodiversity.”

In some Oregon basins, Aldous said, nearly every spring-fed oasis has been tapped to water livestock, often in a way that damages or destroys the wetland.

“There are best management practices, but based on what we see, those aren’t always followed,” Aldous said.

As cattle sip from the springs, farmers tap ever deeper into aquifers that supply them.

The lure of profit generates the thirst. Without water pumps, the vast deserts of eastern Oregon could grow little other than dryland wheat. Irrigated crops are far more lucrative.

State regulators more than a century ago began issuing rights to directly siphon Oregon’s rivers without data to show how much the rivers could give. Today, irrigators routinely drain streams before all farmers with water rights can quench their fields. Many have turned to well water as a fresh supply.

Today’s irrigation wells bear little resemblance to ancient versions, those stone-lined holes in the ground with buckets to extract water. New models are products of modern engineering, capable of pumping gallons per second from fathoms below and spreading it across acres of tilled soil.

In a typical farm setup, electric motors force the water into massive wheeled sprinklers known as center pivots. Each pivot’s long arm protrudes from an anchor at the center of a field, orbiting around it in circles up to a half-mile wide. When viewed from an airplane, the resulting green fields create the appearance of a landscape stamped with bingo markers.

Landowners gain the right to pump by applying for a permit. It sets an amount that the holder is entitled to pump on a specific piece of land. Once owners start pumping, they can obtain indefinite rights to the water. Buy the land and you buy the water rights.

The Dufur Valley, in farm country along Fifteenmile Creek south of The Dalles, has historically been a dryland wheat farming region. But in recent years, many of the wheat farms have become cherry orchards with the help of wells dug deep into the underlying basalt rock.

Regulators have authorized more than 17,000 irrigation wells across Oregon, about 1,400 of them since 2000. Every drought brings a bump in drilling, despite construction costs that can rise into the hundreds of thousands of dollars. The water is used to grow sweet cherries sold at Portland markets, potatoes fried in fast food restaurants across America and alfalfa that feeds dairy cows around the Pacific Rim.

Obtaining a permit to pump has always been surprisingly simple. Check off some boxes, pay fees starting at about $2,000, and you’ll generally get a permit by mail within a year. In fact, the water resources department counts among its key performance goals “timely service to customers.” The department strives for 80 percent of water users reporting they received “good” or “excellent” service.

After your permit is issued, the water itself costs you nothing but the price of electricity to pull it to the surface.

However, the state’s understanding of the underground resource hasn’t kept pace with the clamor to tap it.

Information Void

Oregon lawmakers voiced noble intentions in 1955 when they created the state’s first legal protections for the underground water supply, aiming to preserve it for posterity.

Legislation pushed by Rep. Charles A. Tom, R-Rufus, declared groundwater a public resource to be allocated on a first come, first served basis. Legislators directed state water managers to move “as rapidly as possible” to measure aquifers beneath all of the state’s 18 drainage basins.

Six decades later, the state has completed full studies on three.

Not only have such studies been slow in coming, they happened in reaction to crisis. Landowners asked for water rights. Regulators approved them. Only after overuse created conflicts did the state compile data to confirm wells were draining aquifers or robbing rivers.

For vast stretches of Oregon that scientists have not yet studied, the next best thing is a cursory federal survey nearly five decades old. The 1968 report by the U.S. Geological Survey has not always held up against more thorough studies of individual basins, sometimes drastically under- or overestimating the water supply.

State officials referenced the 1968 estimates last year in explaining why they halted new permits across a large swath of Harney County.

“We used it because there really wasn’t anything else available,” said Gall, the state groundwater manager at the time.

The Oregonian found that the Harney Valley was one of nine key agricultural areas across eastern Oregon where ranchers are allowed to pump more than is available underground. Permitted withdrawals in the Harney Basin total more than 96 billion gallons a year. The 1968 study shows precipitation adds back only 85 billion gallons a year.

“It’s not like the Harney aquifer is going to be the last one,” said Whitworth, of the Freshwater Trust. “We’re overdrafting everywhere and the state has no ability to track it.”

Other Eastern Oregon agricultural communities have begun raising concerns.

In a December request for state money, a John Day Basin group noted the region’s wells are losing water at a “noticeable and alarming” rate. Concerns have also arisen in the Powder Basin, where Baker County Commissioner Mark Bennett sought answers from the state after hearing about Harney’s woes.

Bennett is the administrator for Unity, a city with three wells to supply water for its 71 residents. A growing number of neighbors are looking to dig wells and start cultivating hay.

“The city doesn’t have any money, so how would they pay to deepen their wells if these other folks drilled and sucked all the water down?” Bennett said.

He said state officials told him they would add the Powder Basin to the list of places in need of new groundwater research.

Studies to establish a basin’s profile cost $3 million to $5 million and can take about five years. They reveal the aquifer’s shape and size, its capacity and its “recharge rate,” or how much water seeps in each year. They also tell regulators where the water comes from and where it’s headed.

Lacking more precise estimates of how much pumping aquifers can tolerate, regulators track water levels in about 1,000 government and privately owned wells and wait for signs the water table is dropping.

The Oregonian examined 130 wells east of the Cascades for which long-term data exists. Three-fourths showed declines in recent decades, ranging from a few inches to hundreds of feet.

Regulators caution that the result is hard to interpret because observation wells are most plentiful in places with known groundwater problems.

In parts of Eastern Oregon, a dozen observation wells might be the only source of information in an area the size of Connecticut. A state push to build more of these wells has inched along, with two dozen constructed since 2012.

“One of the challenges is, nobody really measures water in Oregon,” said Todd Jarvis, director of the Institute for Water and Watersheds at Oregon State University.

Although the state knows how much irrigators are entitled to pump, not everyone who owns a water right uses it fully. Conversely, some may be using much more than they are allowed.

Regulators admit they have no way to know either way, because only in the 1990s did Oregon start requiring owners of large new irrigation wells to report how much they pump. Five out of six wells across the state are exempt.

Pressure to Pump

To some degree, regulators’ hands are tied.

Lawmakers control the Water Resources Department budget, and dollars to pay for groundwater research and data have come in at a trickle.

Natural resource concerns frequently get less attention than education, health care and social services – issues more visible, more immediate, and viewed as more important to Oregon voters.

“Until there’s a crisis, people will say there’s no reason to spend the money,” said Rep. Cliff Bentz, R-Ontario, who last year unsuccessfully lobbied for a statewide examination of aquifers and a financing program to help homeowners deepen wells that had gone dry. The bill never made it out of committee.

Water resources department officials in the past two years have received $550,000 to do a job that is expected to cost $45 million to $75 million.

John DeVoe, executive director of the conservation group WaterWatch, calls it deliberate ignorance on the part of state lawmakers. He said they worry if they fund the science, they’ll be forced to acknowledge the limits of Oregon’s water.

The system is “designed, quite intentionally, to be unable to make sustainable groundwater management decisions,” DeVoe said.

Enormous public and political pressure to keep the water flowing drives the state’s failure to regulate groundwater more tightly.

When aquifers start drying up, irrigators file lawsuits. Their elected representatives have held budgets hostage and pushed bills to thwart potential crackdowns on water use. Landowners have threatened violence against water managers who stepped in to address declines.

Pressure to keep wells pumping also comes from inside the department.

Agency leaders are sometimes slow to stop doling out well permits, even when their data shows declining water levels and impacts on lakes and streams.

They’ve opted against further restrictions for the Umatilla Basin, despite acknowledging measures they imposed in the 1980s and 1990s have failed to prevent further drops in the water table.

And in the Klamath Basin, regulators continue granting pumping permits to help irrigators cope with shortages of surface water, despite conceding that the water table is already stressed beyond its sustainable limit.

“They have the authority to stop it, and they haven’t exercised that authority,” said Jackie Dingfelder, a former state representative from Portland who lobbied for more restraints on groundwater use. “It is a classic case of the iron triangle, where they’re beholden to their stakeholders and it’s difficult for them to say no.”

People who advocate for restrictions on water use say they regularly face off against industry lawyers and consultants who once worked for the department. The list of former employees who have since become consultants or attorneys for water users includes a former director, a policy analyst, a senior policy analyst and a mid-level manager.

“Their attitude for a long time has been to view water users as customers, worry about their needs, and say ‘yes’ whenever possible,” said DeVoe, leader of WaterWatch, which has brought numerous lawsuits against the state over water management.

In Harney County, land permitted for groundwater use skyrocketed from 60,000 acres in 2005 to 95,000 acres last year. The state steadily approved new pumping despite warnings from agency scientists nearly 10 years ago that the valley’s water table could be dropping.

Only after multiple complaints from WaterWatch did the state stop giving out more water permits last year. Agency leaders now concede they may have given out access to more water than the system can sustain.

While the state conducts a five-year study to test that hunch, uncertainty looms over ranchers and residents who use well water to drink, bathe, and nourish fields of alfalfa. They wonder whether the state’s study will bring bad news or good. They’re not sure they can trust the results.

They worry their wells will go dry while they wait.

This article originally appeared in the July 26, 2016, issue of the Oregonian’s Draining Oregon series.